Nothing Natural: The Art of Peter Wilson

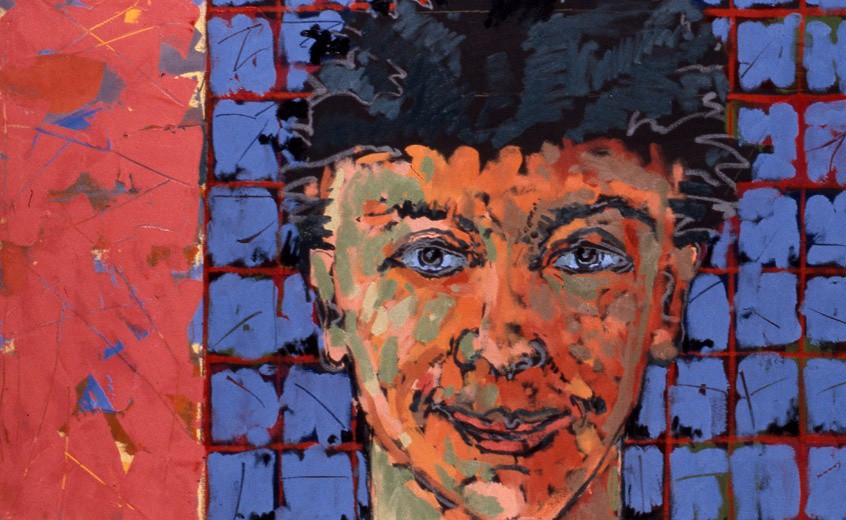

Don’t be misled by the unashamed directness of the title to this exhibition, ‘Instincts: Lost and Found’. There is nothing direct and certainly nothing natural in these teasingly artful paintings, which are haunted by the fears and desires of the body, and yet shy from directly picturing it.

Even the elements which seem drawn directly from nature, the crustaceans, fish, molluscs and insects, turn out on inspection to be something other than homages to natural history drawing. Up close, the molluscs look more like Jasper Johns’ target paintings, the abdomens of insects more like the stripes from a Kenneth Noland, and the fish owe more to Freud rather than to angling.

If an analogy for the paintings in this show is wanted it would be better drawn from music than nature. They are contrapunctual paintings, placing a human head in dialogue with the body of a crustacean, and counterpointing a section of gestural abstract expressionism with a line drawing of a fish made directly into the paint. They set up dialogues between nature and art, surface and interior, representation and abstraction, and decoration and function.

If sources and antecedents for this witty, haunted art are wanted, some spring to mind. Most obviously, there is surrealism, with which Wilson shares obsessions. There is the preoccupation with anxious masculinity, interior landscapes, startling juxtapositions, boundary crossing; there is also a common fascination with psychoanalysis and a love of strange and fascinating creatures into which desire and fear can be projected (Dali’s ‘Lobster telephone’; Klee’s fish).

But there is also the matter of Peter Wilson’s Scottish ness. After all there is a long Scottish Calvinist-led tradition, from Hogg’s ‘Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner’ onwards, which is drawn towards and repelled by instinct, is torn between abandonment to the sensuous and recoil from it.

But perhaps more important than sources or antecedents is the way the paintings tap into profoundly contemporary concerns with the body. The horror films of David Cronenberg and the ‘Aids’ paintings of Ross Bleckner come to mind. But this is where Wilson’s true originality lies. His paintings don’t strike Cronenberg’s tragic pose, nor do they rush to embrace nature as advocated by Robert Bly’s ‘Iron John: The paintings in ‘Instincts: Lost and Found’ are shot through with wit – in them, male fears and desires are never far away from the comic and pathetic. This is something most men repress.

Philip Dodd, September 1992.

Philip Dodd was editor of Sight & Sound, and co-author of Relative Values; or what’s art worth. Director of the ICA , contributor to BBC Arts programmes and Art Monthly, Modern Painters, Screen etc.