Glasgow boy on the beach

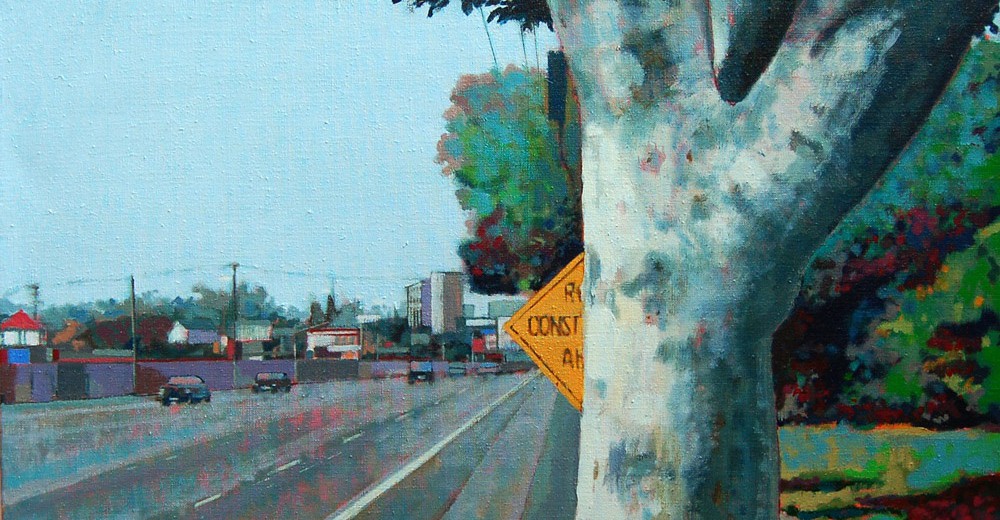

Peter Wilson’s latest paintings announce a surprising stylistic and thematic departure. After the graphic, stream of consciousness works we are used to his work has become descriptive and knowingly mannered. One picture will comprise contrasting brushwork – much of it flat, betraying the influence of abstraction, but supplemented with lively passages that give a sculptural solidity to trees and buildings and add volume and intensity to the shadows. Curious pictures, the light doesn’t seem to belong to these optimistic skies, the colours are heightened – saturated. Maybe the people are hiding from the intensity?

The era of painters painting views is over. Photography has not only assumed the mimetic function; it has imposed its own special language and codes. Wilson’s paintings mimic the conventions of photographic representation, but then eschew the minutiae. They seem to have been conceived with one eye shut with their fixed viewpoints, frozen moments, and incidental yet telling details. These seem to be the labours of a flaneur In fact each painting was adapted from a black and white photograph taken by Wilson. Like other painters of his generation, Wilson has used photographs in different ways to reinvest painting with relevance while rejecting what Gerhard Richter has called “the heritage of European painting derived from Cezanne.”

Most photographic of all is the subject matter itself. The everyday, the urban, the mystery of the familiar – this is the terrain that photography claimed for itself. The AA Liquor Store with its toppling pole, anecdotal traffic light and plane hanging in the sky comes right out of a Lee Friedlander photograph of the 70s. Camper on Driveway borrows the fussy cropping, deadpan gaze and iconography of the “new topographies” photographers – among them Joe Deal and Lewis Baltz. In the 70s they set out with their tripods for the new West to chart the ugly liminal spaces where suburbs and sprawling industrial parks met nature.

It is important to know that the paintings were adapted from Wilson’s photographs because it tells us that this work is not wholly invented; that these places were not copied from a real estate brochure or a skateboarding magazine. It tells us that the paintings are partly informed by direct experience of place – albeit one no doubt mediated by an odd sense of familiarity that relates to what Barthes termed deja-Iu (“already read”). The photographs were made during several trips to LA over 7 years, often to see his friend, the filmmaker, Ian Conner. In fact the work comes out of a condition of being in between: between LA and England, between photography and painting, between experience and remembering. The paintings are therefore more about imagination, fiction, allusion and much less about observation. This is consistent with Wilson’s work to date, for all of it comes from the rich and subversive world inside the artist’s head.

Peter Wilson’s paintings are adapted from photographs of places, which are well known because of photographs. These intersections, beaches and suburban streets of LA might be thought of as the Rouen cathedral and Mont. Sainte-Victoire of the age of celluloid. Backdrops to countless Hollywood dramas, they are now screens onto which Wilson projects his fantasies, memories and premonitions. They are the imaginings of someone who began painting when the megalith of American culture began overshadowing Europe. Its jazz and blues, literature, Hollywood noir and myths formed the sensibilities of his generation.

One recent painting, Ghost Car, features a car concealed under a dust sheet. It is prefigured by a similar image from Robert Frank’s book The Americans 1 called Covered Car – Long Beach, California. Frank, a Swiss photographer and filmmaker, passed this way in the late 50s, gathering images for his classic portrayal of under-belly USA The critic, Jim Lewis has described the America of The Americans as “dazzlinglyanti-sublime”2.

Peter Wilson’s copy of the book is well thumbed. He has found a passage in Jack Kerouac’s famous introduction in which the writer alludes to Covered Car.

“Car shrouded in fancy expensive designed tarpolian (I knew a truck driver pronounced it ‘tarpolian’) to keep soots of no-soot Malibu from falling on new simonize job as owner… snoozes in house with wife and TV, all under palm trees for nothing, in the cemeterial California night…”

Wilson likes this invoked scenario about a car and its owners shrouded and sealed from dust and life. It illustrates what he likes about Frank and maybe about art in general – which is the fictive power of the image. The emptiness of The Empty Quarter is an invitation to dream.