Immersed in Film Sight and Sound Jan 93

Artist Peter Wilson peers into the depths of his past, catching glimpses of the Toledo cinema in Glasgow, strange creatures from the deep – and the films of etymologist Luis Buñuel

“Don’t worry if the movie is too short, I’ll just put in a dream”. Buñuel talking to a Mexican film producer.

Since childhood I’ve had a recurring dream that seems to surface at odd times.

The setting is based on a redundant water tank behind a cinema I used to visit when I was a kid living in the suburbs of Glasgow. The water tank was large, and seemed to occupy an area equivalent to a tennis court. The water tank was constructed from concrete and resembled a shallow swimming pool. The pool collected rainwater to a depth of a couple of feet and was cordoned off with a low wire fence, with gaps between the mesh. The surface of the water that collected in the pool changed with the seasons.

It was the neighbourhood home for frogs and toads. The surface changed from brown to an acid green with slime-encrusted walls during hot weather. It is imposible for me to verify its exact dimensions as the area was redeveloped into a car park and then a supermarket.

Cinema habits were different in the early 50s in Glasgow than they are now. It was possible then to get into a cinema and watch complete programmes, newsreels, forthcoming attractions, a backing film and the main feature two or three times around. This meant you could stay in the nocturnal world of the cinema for six to nine hours. I suppose it was an act of endurance, and after marathon viewing sessions new records for daylight deprivation could be flaunted to schoolmates. This phenomenon was reminiscent of how long you could stay underwater holding your breath at the local swimming pool.

Sensory deprivation

I was reflecting recently on this early sensory deprivation and musing on how the excesses are necessary in marking out stages in one’s doubtful development. The image of the water tank at the rear of the cinema and the screen in the cinema seemed to be connected. The two surfaces – the cinema screen and the disused tank – were about the same size, one surface vertical and the other horizontal. Visiting the water tank when I didn’t have enough money to immerse myself in the film was a substitute, and I often wondered what lurked below the tank’s murky surface. It was not until I went to sleep that the underwater cinema came alive. In the dream, the water appeared initially to be still. but on further gazing the surface started to undulate, revealing dark shapes reminiscent of a kind of fish that didn’t appear in any of the National Geographic magazines that the fortunate at school were allowed to read after ,successfully answering questions about far-away countries. The shapes continued to move up to the surface of the pool and strange fins pierced the surface, sometimes revealing teeth and jaws. The size of the beasts increased and paralysed me as I watched from the side of the pool. The performance continued and each subsequent appearance became more grotesque: I froze in wonderment and fear at this display from the deep. Over the years, the dream has featured less frequently, but has re-emerged and fused into a series of paintings entitled Under the Surface, Toilers of the Deep, and Instincts Lost and Found, To kill or not to kill The cinema in Glasgow still exists, but now it has been divided into several smaller cinemas. When I remember the cinema of my youth, it had white rough-cast cement walls that betrayed a strong Moorish architectural influence. The cinema was called the Toledo and was part of the old ABC chain.

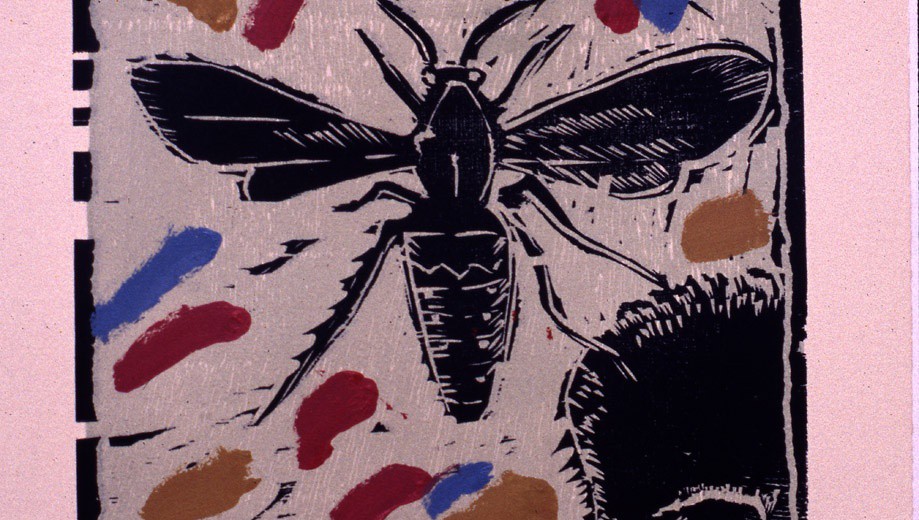

The Spanish theme was carried throughout the building, including bullfighting scenes on the tiles in the lavatories and Spanish shawls hung from the false balconies that were a feature on the side walls of the stalls. This extravagance culminated in elaborate silk and velvet curtains that protected the silver screen. The curtains had applique butterflies and stars and resembled an outsize dressing gown. As the house lights in the cinema dimmed, this curtain swished open silently to reveal the screen. preparation for the later viewing of Bunuel’s work in art-house conditions: or maybe it was the musings by the derelict water tank that fuelled the imagination of an ex-ABC Minor?. The Bunuel connection is more than casual, and aspects of his filmmaking have influenced my work. Before Bunuel started making films he studied etymology at the University of Madrid – his use of insects in ‘Un Chien Andalou’ is fascinating.

“To kill or not to kill an insect is a decision which faces several characters. It is morally all the more indicative as the act involves no retaliatory consequence, because it is a matter of impulse rather than reflection, while from conventional viewpoints it has no moral significance. Thus the insect motif sometimes suggests a reverence for life. But this reverence is amused and sardonic. The sudden death of an insect can also imply that the man can die as abruptly, and as unimportantly”.

“Further, the cut-ins of insects with the omnipresence of animals generally throughout Buñuel’s films jolts us by its reassertions of the ubiquity, the viability of alien modes of instinct by a planet which ludicrously we tend to think of as ours”,

(Raymond Durgnat, Luis Buñuel, 1967) This article for Sight and Sound was requested by Philip Dodd who also wrote the catalogue essay Nothing Natural : The Art of Peter Wilson,for my show Instincts Lost and Found.

Peter Wilson’s exhibition ‘Hunger & Thirst’ was shown at the Lamont Gallery, London from 12January to 13 February 1991. Peter Wilson Jan 1993